What a VC learnt from the 600 start-ups he said “NO!” to

This report is based on research carried out by William McQuillan, partner at VC firm Frontline. He faced the same problem as any other VC, which is how to reliably predict a company’s performance given that exits take more than 8 years on average and an investor’s portfolio is too small of a dataset to make any accurate prediction.

Rather than basing his models on his 15-company portfolio, McQuillan decided to analyse the hundreds of companies he decided NOT to invest in. From a total of 2,684 B2B companies that he personally saw, he selected the 600 that he had a chance to meet in person or speak to over the phone, in order to employ more precise criteria for his analysis.

The Analysis

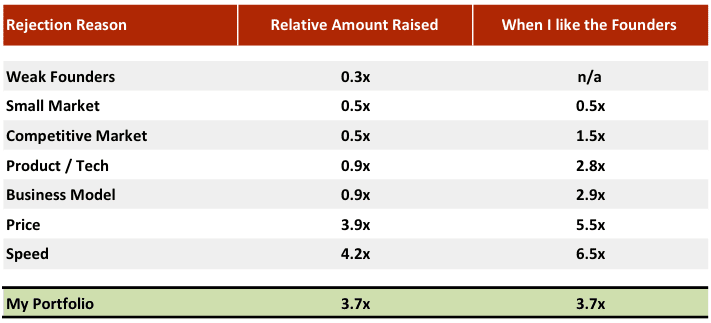

For each company, McQuillan noted why he said “no”, and paired the data with the average investment received by the same company over time.*

*calculated as the total investment received divided by the number of months since their meeting

The average investment received, in this instance, is used as an indicator of success, even if – as noted by the author – this does not 100% reflect reality.

The companies were then grouped based on the reason for declining their offer between 7 main groups as follows:

- Weak Founding Team

- Small Market

- Competitive Market

- Product / Technology

- Business Model

- Price (i.e. valuation was too high)

- Speed (i.e. deal closed too fast for the VC)

The results were then normalised to the overall average (being $89k invested per month). So a multiple of 0.5x for example, means that the group raised on average $44.5k, which is half of what the average company raised.

A sub-group was also created to include companies with a team that McQuillan regarded as particularly strong.

Finally, the author put the results of his portfolio as a point of comparison.

The Results

Weak Founding Team

The single most influential factor for rejection is a weak founding team. This is common knowledge that is now backed by data. Weak founders receive on average 30% of funding compared to the average company.

Companies with strong teams, on the other hand, raise between 2 and 3 times more than comparable companies that have been rejected for the same reason and, in most case, several times more than the average. This seems to indicate that the founding team has more impact on a company’s success than many other factors including its product, business model and market.

Small market and Competitive market

Small-markets and competitive markets are two other common deal-breakers in the VC world. This analysis seems to confirm the rule of thumb. In both cases companies that were rejected for these reasons went on to raise half of the average company.

This is also true with companies with great teams operating in small markets, but not for those facing high levels of competition. This infers that a strong team might encourage investors to bet on a company regardless of the competition because it’s perceived as superior and investors feel confident that it’s going to thrive.

Product/Tech and Business Model

Results from these two factors were very close to the average company raise. This led the author to two possible conclusions:

- Since most of the investments made my McQuillan’s VC firm were at seed stage, often pre-product and pre-revenue, Business Model and Product are simply not good indicator of the success of a company at that stage.

- On the other hand, since this is McQuillan’s personal judgement as a VC, it could just mean that he is not particularly skilled at spotting a good or a bad product or business model.

Price and Speed

Some companies that were rejected for either being priced too high or if the deal was moving too fast for McQuillan’s firm went on to raise more than the author’s portfolio.

For price, this meant that the author’s fund has “missed out” on some deals because they were too price-sensitive. These company eventually went on to raise more capital than the author’s portfolio.

Speed, on the other hand, is more interesting. It indicates that the firm missed out on some good opportunities because they couldn’t move quickly enough. Frontline VC is certainly not the only VC firm that is taking “too long” to complete the due diligence for its investment, resulting in deals closing before the firm can make a decision. While many funds handle pensions and savings monies on behalf of institutions and therefore selection process rigour is rightly required, perhaps some may need to be fast tracked for FOMO!

The information available on this page is of a general nature and is not intended to provide specific advice to any individuals or entities. We work hard to ensure this information is accurate at the time of publishing, although there is no guarantee that such information is accurate at the time you read this. We recommend individuals and companies seek professional advice on their circumstances and matters.