All The Red Flags Behind WeWork’s IPO

How could we not talk about WeWork going public? What has been one of the most highly anticipated IPOs is quickly turning into a complete disaster as most media outlet called out the office space company for a whole array of suspicious practices within the company. One analyst described the initial S-1, filed on August 14, as a “masterpiece of obfuscation“.

At the time of writing, there is no official information about stock pricing, but while the company was valued at $47bn in its latest funding round led by SoftBank, some now fear that the negative publicity will bring that down to $15bn: less than the money that has been invested in the company.

We identified five key red flags that summarise what isn’t working with the company. And while there’s no way to know whether the sceptics will be proven wrong (yet!), we’re here to explain why you should try and avoid WeWork’s mistakes.

1) No Innovation in the Business Model

WeWork was born in New York City in 2010 with the purpose of providing co-working space to a target including mainly freelancers and small start-ups. Since its founding, the company grew at rocket speed, operating 528 locations in 111 cities and 29 countries 9 years after its foundation. This has certainly been sped up by the $12.8bn in funding received over 14 funding rounds, mostly led by SoftBank, which owns around 30% of the company.

Even though WeWork likes to refer to their offering as “Space-as-a-Service”, the core of their business model is not at all new. As Forbes contributor and CEO of research firm New Constructs David Trainer pointed out, a Belgian company called IWG operated the same business model of sub-leasing office space under short terms after having leased and refurbished it, and it has been since 1989.

IWG is actually listed on the London Stock Exchange, so its market cap is known and, at $3.7bn, it’s around 12 times smaller than WeWork’s latest valuation.

How so? From a financial point of view, that is very unclear: IWG operates around 20% more usable square feet of office space than WeWork and it earns hundreds of millions in profits every year, while WeWork keeps posting losses (more on this below).

Of course, you could argue that a higher valuation would be justified by the considerably higher engagement of WeWork’s community which is supposed to generate more revenue streams in the long-term, with the company finding new way of capitalising on its existing platform Amazon-style. However, it’s hard to justify a valuation that’s 12x higher than a comparable company with all of these assumptions.

2) Reckless Risk Exposure

A key issue with how WeWork is run is the extremely long lease terms that they keep underwriting to fuel growth. The average lease term for a WeWork location is 15 years. Additionally, most (71%) of WeWork’s current lease obligations are due after 2024; these amount to $24.1bn.

That is a huge sum that The We Company will have to pay in the somewhat distant future. Definitely too far beyond revenue forecasts can reach. In addition to that, the company uses an extremely high discount rate (8.2%) to calculate the present value of their operating leases, which allows them to understate the value of their debt.

Just to give you some point of comparison, just 37% of IWG’s lease obligations are due after 2024 ($2.5bn vs WeWork’s $24.1bn), with IWG using a more conservative 3.7% discount rate.

The real shortcoming of this strategy emerges in the event of an economic recession. With over $47bn in rental commitments (just as much as the company wishes it was worth!), most of which relative to locations across the US and in London, the company’s ability to pay rent relies on its own tenants.

But what happens if the US or the UK enter a recession? Companies would cut staff and reduce office space, and WeWork’s value-adding services such as IT support and enhanced amenities would likely not be enough to justify the price premium. In such conditions, The We Company would be very unlikely to afford the rent it’s already committed to pay.

But how can a company afford to expose itself to such a high risk? Easy: as reported by the Financial Times, landlords have very little recourse in case the WeWork fails to pay, as per leasing terms.

3) Unclear Path Towards Profitability

There is no doubt that WeWork has managed to achieve incredible growth: revenue increased from $886m in 2017 to $1.8bn in 2018, but it came with a price, with losses also increasing from $1.2bn to $2.2bn.

As most tech companies facing mounting losses do, WeWork blames these costs on growth. The problem with that is that the company’s contribution margin is actually decreasing. This means that in the first half of 2019, the average profit margin excluding all fixed costs was only 25%, decreasing from 2018’s 28%.

The fact that the company is moving further away from profitability in a time of prolonged economic expansion both in the US and in most of Europe (WeWork’s main markets), in addition to what we mentioned about risk, is a clear red flag signalling a flawed business model.

4) Questionable Corporate Governance

One of the main concerns raised by investors over WeWork’s IPO is its dual-class of shares, which essentially does not give public investors any control over the company. Such control is in fact held solely by WeWork CEO Adam Neumann.

What’s even more concerning is Neumann’s personal history of personally profiting off the company’s back.

- Owning buildings where WeWork is a tenant. Neumann is his own company’s landlord and has collected rent from it for years. The company plans to address this clear conflict of interest by transferring Neumann’s holdings into a new entity called the Ark Master Fund (owned by WeWork) which will take ownership stakes in commercial real estate. Still, the fact that this obvious conflict was allowed to persist for so long raises serious questions as to how the company prevents similar conflicts from occurring.

- Borrowing from WeWork. The company has lent money to Neumann personally and to his personal LLC at interest rates under 1%. These loans have all been repaid, but the below-market interest rates suggest Neumann was getting a clear benefit.

- Employing family members. Several members of Neumann’s family are employed by the company, including wife who is a co-founder of WeWork and serves as the CEO of the company’s education business, WeGrow. The company also paid another family member to host events related to its “Creator Awards” in 2018.

- Charging for the “We” trademark. In July, the company paid Neumann’s personal LLC $5.9 million in stock for the rights to the “We” family of trademarks, in the context of its re-branding to The We Company.

Some of these concerns are already being addressed by the company, amid weak investors’ demand. Neumann’s voting power is being reduced along with his family’s control over the company.

Nonetheless, Neumann seems to be using the company’s IPO as another way to profit, having a personal line of credit of up to $500 million from UBS, JPMorgan, and Credit Suisse, all of whom are coincidentally underwriters in WeWork’s IPO. Such line of credit is coincidentally secured by his holdings of WeWork stock. As per terms of this credit agreement, if the stock price declines to a certain point, the banks can claim and sell some of Neumann’s stock. This means if the IPO goes poorly, the underwriters themselves might become sellers and contribute to the stock price decline.

Each of these factors contributes in shifting all of the IPO risk onto the public investors, while the CEO and the underwriters will have already cashed out hundreds of millions.

5) Exaggerated Valuation

Finally, the main reason to be concerned about the WeWork IPO is certainly its stellar valuation.

How unrealistic WeWork’s private markets valuation really is, becomes apparent when we compare it with one of the largest Real Estate Investment Trusts (REIT) on the planet: Boston Properties.

Boston Properties’ current market cap is just over $20bn, earning almost $1.7bn in Gross Profit last year.

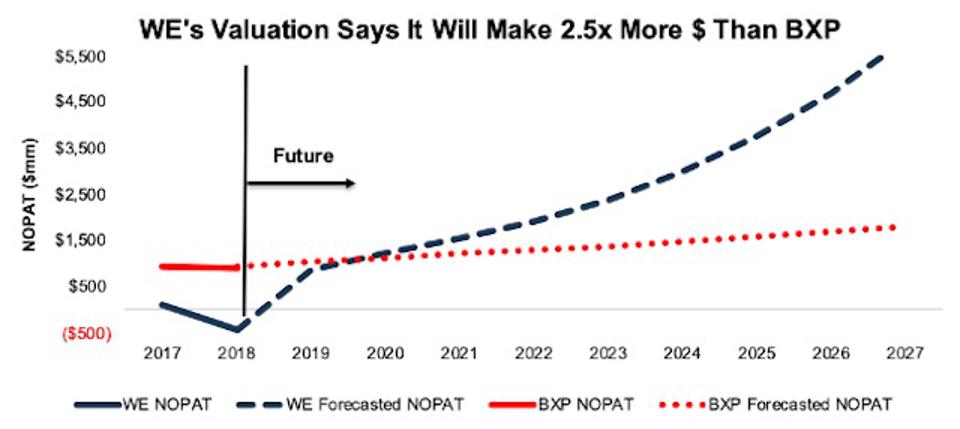

We’ll spare you the maths, but in order to justify its latest official valuation, WeWork would have to achieve the same Net Operating Profit After Tax (NOPAT) margins as BXP (around 30%) and grow revenue by an annual compounded rate of 30% over the next nine years.

Considering that WeWork’s current NOPAT margin is negative, that seems like an optimistic perspective – to say the least. Moreover, thanks to the magic of compounding, any annual growth rate that is lower than 30%, would make the company’s valuation a fraction of its latest one.

The information available on this page is of a general nature and is not intended to provide specific advice to any individuals or entities. We work hard to ensure this information is accurate at the time of publishing, although there is no guarantee that such information is accurate at the time you read this. We recommend individuals and companies seek professional advice on their circumstances and matters.