Capital Efficiency: Do Larger Investments Make Better Businesses?

Anyone who has been close to the startup ecosystem for more than a few months will have noticed how the typical Funding Round is getting bigger and bigger – especially those we hear about in the news. Megadeals, Funding Rounds worth over $100m, have indeed tripled between 2016 and 2018 according to CB Insights. Such a strong trend begs the question whether this sharp increase in funding is actually leading to superior returns and more successful exits. In this report we will explore the concept of capital efficiency to understand whether larger investments actually help companies to succeed.

Before deep-diving into the consequences of this phenomenon, however, we need to think about where these huge amounts of cash are coming from.

First and foremost, SoftBank Groups’s Vision Fund played a key role in transforming these megadeals into the “new normal” for ambitious companies. With over $100bn in capital, the fund has been basically throwing money at anything that moves, as long as they are moving up and quickly: from Alibaba to Zymergen, through DoorDash, Lemonade, WeWork and Uber – in which the fund poured a staggering $7.7bn pre-IPO – SoftBank took no prisoners and set the trend for other funds to follow.

Leading VC funds such as Sequoia Capital, New Enterprise Associates and Accel have all followed SoftBank’s lead and announced $2bn+ funds in the past year. While such amounts pale next to the $100bn Vision Fund, Sequoia’s new $8bn fund represents a 4x increase compared to its previous largest-ever vehicle.

This lavish approach to investment took Silicon Valley by storm and quickly spread across the global Venture Capital ecosystem, but is it grounded in reality? What kind of returns do these generous investors get, and do these massive cash injections actually help growing business achieve more in less time? CB Insights looked for the answer in their data about over 500 VC-backed US tech companies that have exited for more than $100m since 2013.

“Low-Raisers” (with less than $100m in VC funding) were compared with “High-Raisers” ($100m+) based on their valuation at M&A or post-IPO.

The result reveal many of the underlying problems of today’s overfunding craze that are hidden in plain sight within the data.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- After IPO, the most highly funded startups tend to underperform those who raised less.

- In fact, the companies that raised the most almost uniformly struggled to create long-term growth.

- Plenty of companies that raised <$100M have seen top exits.

- The biggest exits, backed by the deepest-pocketed investors, are returning less and less as foie gras’ing becomes more common — and more extreme.

- Exceptions like Facebook (both lavishly funded and successful) tend to get most of the attention due to survivorship bias.

Read on for a deeper analysis.

Overfunding VS Long-Term Performance

The first finding of CB Insights’ Research is that High-Raisers almost uniformly struggle reaching long term growth post-IPO, and are consistently outperformed by Low-Raisers.

Specifically, the median post-IPO increase in value for Low-Raisers was 263%, compared to an only 64% median increase for High-Raisers.

For example, 6 out of the 11 highest valued high-raise companies — Snap, Groupon, Dropbox, Zynga, Lending Club, and GreenSky — have registered a negative change in value since their IPO. For companies that have seen an uptick in value, growth has been limited: Twitter and Zayo Group Holdings have seen growth of less than 100%, while DocuSign has only done slightly better

But among the low-raise cohort, it’s a different story.

Six of the 9 most highly valued startups at IPO that raised less than $100M — Veeva Systems, Palo Alto Networks, ServiceNow, Tableau Software, Splunk, and Ubiquiti Networks — have tripled their valuations since going public. ServiceNow’s value has increased nearly 1,900%, while Ubiquiti Networks’ has increased roughly 800%.

The most obvious explanation of these data is that High-Raisers went through much more generous Funding Rounds at higher and higher valuations to avoid dilution across shareholders. This meant that at their IPO they already had big expectations to satisfy, and while increase in stock price is largely driven by companies exceeding shareholders’ expectations, High-Raisers just weren’t able to do so by the time they went public.

Overfunding VS Exit Valuation

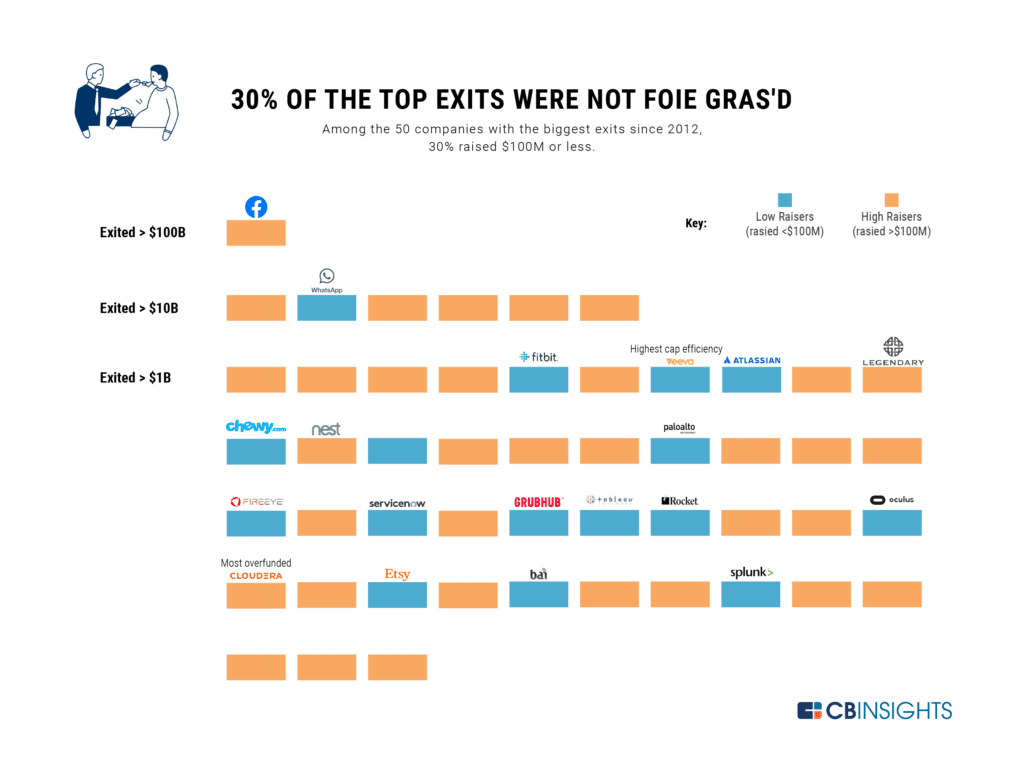

It would be reasonable to assume that top exits within tech startups would be dominated by High-Raisers. After all, higher investment should equal higher returns. However, that assumption does not seem to match reality. In fact, 16 companies out of the top 50 exits since 2012 had raised less than $100m.

The most “capital efficient” company on this list was VeevaSystems – a cloud computing company focused on the pharmaceutical and life sciences sector. With just $4m in funding, VeevaSystems went public at a $4.4bn valuation.

While this little-known company is obviously an outlier, there are some much more high-profile names among the Low-Raisers who achieved Top 50 exits: WhatsApp, Fitbit, GrubHub, Oculus and Etsy are just some examples.

The top exit in the sample was Facebook’s $100bn+ IPO in 2012, with the Menlo Park company being the best example of a High-Raiser achieving a proportionally successful exit.

Overfunding VS Capital Efficiency

Investing in start-ups recently became common practice outside the somewhat restricted circle of VCs that have been curating their portfolio for decades. Banks, sovereign wealth funds, asset management firms are all writing checks for the next big tech.

As investment rounds got bigger, valuation started growing as well, although not quite at the same pace. Investment amounts outpacing exit valuations translate in a lower return on investment.

The Exit-To-Raise multiple (or capital efficiency) is often used as a metric of how well a company is able to turn it’s investors’ capital into shareholder value. Examples of capital-efficient start-ups include WhatsApp and Atlassian, which both achieved multibillion-dollar exits with relatively little investment.

Others, like Snapchat or Cloudera, did not manage to achieve comparable exits in proportion to the huge amount of funding they received.

Overall, the latter seem to be the most common scenario. In just five years time, between 2013 and 2018, Exit-To-Raise multiples have been sensibly decreasing across all ranges, but exits above $1bn took the hardest hit.

In fact, in 2018, medium-large exits ($500m to $1bn) had higher capital efficiency than $1bn+ exits. They had an average return of 8.9x in 2018, just below their 2013 ratio of 9.7x.

However, the average multiple for unicorn company exits has fallen from 16.1x to 6.9x — a 57% drop in just 5 years. That’s the difference between a company that raised $500m selling for $8bn and the same company selling for just $3.45bn.

Why Overfunding Is An Issue

Even though the data clearly shows that larger investment do not lead to higher returns, investor show no intention to stop the trend. Partly because the current competition requires certain amounts and offering less would mean missing out on some clear opportunities, but most of them justify their “generosity” with the few success stories overpopulating the media.

News outlet often only report sky-high valuations as they are more prominent eye-catchers than in-depth data, but even high-profile exits such as Uber IPO at $82bn valuation represents just a 3.3x multiple on its massive $24.7bn raise over 22 funding rounds. That is less than half the typical capital efficiency for a company of that size, let alone Uber’s clear struggle in achieving a profitable model and a sustainable growth as a public company.

Other less-talked-about exits that underdelivered in terms of capital-efficiency were

- SandRidge Energy ($3.6B at IPO, raised $870M)

- GreenSky ($4.3B at IPO, raised $610M)

- Zayo Group Holdings ($4.5B at IPO, raised $825M)

12 of the top exits in 2018 raised more than $200M, compared to the 7 in 2017 and 3 in 2013, showing that overfunding is becoming the norm rather than the exception.

The real issue with overfunding is that the consistent underperformance of startups in returning capital to investors could damage the investment ecosystem in the long term, establishing ROI expectations that appear deeply flawed when compared to the data, and encouraging an investment approach that puts companies under the massive pressure of unnecessary cash injections rather than allowing them to achieve an exit at a proportionate valuation and possibly continue their growth in the public markets with a long-term view.

The information available on this page is of a general nature and is not intended to provide specific advice to any individuals or entities. We work hard to ensure this information is accurate at the time of publishing, although there is no guarantee that such information is accurate at the time you read this. We recommend individuals and companies seek professional advice on their circumstances and matters.